|

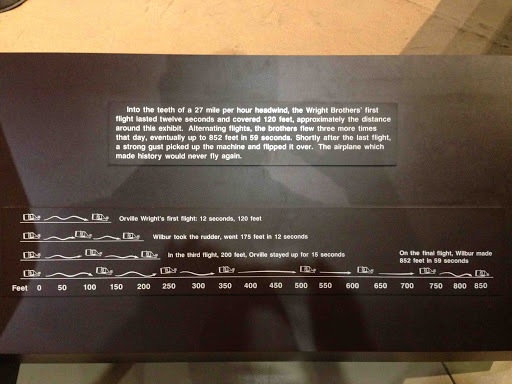

When I think about continuous improvement, I think about this small plaque at the EAA AirVenture Museum in OshKosh, WI.

In 1903, the Wright Brothers made the history books with the first "controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight." Everyone celebrates the first flight, which was 40 yards in about 12 seconds. The most interesting aspect of the day is how much the Brothers improved. By the end of the day, they stayed in the air 59 seconds (391% improvement) and traveled 852 feet (610% improvement). In terms of speed, the first flight was 10 ft/second; the final flight of the day was 14 ft/second (40% improvement).

2 Comments

It was the final class of “Mobile and Web Development.” Twelve teams were presenting their final projects. We were one of them. I was ready to BS my way through a presentation of crudely crafted wireframes, collect my B for the semester, and inch 3 credits closer to graduation.

When I got to class, it all changed. Zak, my partner, took my iPhone 3G, plugged it into his Mac and handed it back to me. “Create an account,” he said. “What?” I said dumbfounded. “Open the app and create an account.” I clicked on a blank icon, entered my email address and was brought to a white screen. In the top right corner of the app, was a “+”. I hit it, which brought me to a new screen asking me to create an album. With my heart beating steadily faster, I typed in “test” and hit “Done.” I was brought to another screen with a camera icon. I took a photo. It uploaded. I then noticed an “invite” button. I hit it and entered Zak’s email into the pop-up box. One minute later a new photo, not taken by me, appeared next to the first photo I took. Viola! A collaborative album. Ditching the PowerPoint deck, we did a live demo for the class. When we were through, I asked: “How many of you would use this app?” About 42 out of 45 raised their hands. We were onto something. At that moment, we had an MVP: a barebones product built quickly that is used to test consumer reaction. Given the positive feedback, the next step was to build an initial product for the market – you know, something thoughtfully designed and rigorously tested. But did we do that? Nope. I was so hopped-up on the lean start-up buzz, that I spent the next six weeks saying “we need to build a Minimal Viable Product.” So we took the barebones design and added to it. Some of the features were sensible; for example, attaching the name of the photo-taker to the photo. Others were unnecessary; posting a photo to Twitter, for example, could wait. In the end, we spent 6 weeks adding features to a “minimal” product that had already tested positively with consumers. That time should have been spent enhancing our design, nailing the user experience, formulating the out-of-the-box experience and testing. Repeat after me: I will stop building an MVP after validating my product with real users and move quickly to building a market-ready product. Last week, Spottah 2.0 was released. The redesign was made possible by the talented Chris Allen. He discovered Spottah at a bachelor party, loved it, and pitched us on a redesign. Two days later, he shipped a reimagined home page. It was stunning. Chris crafted crisp designs and Yin brought them to life. And for the next few months, I had the honor of watching the Lennon/McCartney of app builders compose their masterpiece. Over the past six months, Spottah managed to quiet the "Lizard Brain." It was an amazing streak that would make Seth Godin proud. We delivered a minimal viable product, a beta and two Apple App store releases without thrashing. But like all great streaks, ours came to an end. Between Sunday night and Wednesday morning, we violently thrashed. Think boated Great White.

Without getting into great detail, we planned to push an App Store update on Sunday night. Since releasing our first version in mid-May, we identified a few bugs and “stumble points.” My favorite: Facebook Connect in Norwegian dialect. So we drafted a 20-item requirements list in Pivotal Tracker. One-by-one Spottah’s amazing development team delivered. On Saturday night we received a TestFlight. Every requirement worked. One final call on Sunday to “push the button together.” Sunday. 4PM. The team assembled. We agreed: the new build is tight. We thanked the development team. They, like always, said don’t worry about it. Then it happened. Our partner in charge of the front-end threw out a final request. Our back-end developer said it shouldn’t be too hard, and that he’ll look into it. “Great,” I said. “Look into it. If it isn’t too difficult, go for it.” And so began the thrash. One fix caused four problems. And in the end, the request had the opposite effect: it slowed Spottah down. How did this happen? Why am I so upset that we thrashed? And most importantly, how will the team ensure that this does not happen again? How did this happen? Over-confidence and a lack of discipline caused Spottah’s thrash. During the six months the team has been together, there has not been a single programming challenge that our developers could not solve – quickly. With each precise and timely delivery, confidence grew. Discipline, in turn, waned. After all, why be disciplined in your decision-making when every task is doable? So on Sunday, when the extraneous request was proposed, I had no doubt that the team could deliver. Instead of being a disciplined project manager and asking a line of questions (Do customers want/need this? How will implementing this one item affect other parts of the application?), I resorted to the worst logic in product development: If doable, than do it. Why I’m so upset? I’m upset because thrashing strains the team. The development team bears the brunt of the strain. Developing a beautiful application that is easy-to-use and reliable is difficult, to say the least. Thrashing makes the process more difficult and lowers morale. Who likes investing hours into building something, only to find out after a few seconds of usage that it makes the product worse? And it doesn’t end there. Additional hours are required to undo the now-useless requirement. It’s like building a house, realizing you don’t want to live on that particular street, and then dismantling the house. The business side is strained, too. Since the Apple update process requires deliberate action by the consumer, you don’t want to push the product too hard knowing that an update is in the not-too-distant-future. It makes little sense onboarding people on Tuesday only to ask them on Wednesday to update. Since the business-side is measured by active users (at Spottah, at least) it is stressful to delay marketing efforts. Overall, thrashing harms the team dynamic. While one side of the team burns the mid-night oil, the other is left sitting on their hands. Steps for avoiding future thrashes 1. Invest the time up-front to develop a sensible requirement list….and stick to it! Spottah did the first step. We had a requirement list that addressed bugs, UX improvements and performance. We nailed all 20 items on the list. The one item not on our list led to a thrash. 2. Exceptions to Step 1 can be made but be doubly – no triply – sure you need it. It is naïve to say that you shouldn’t adjust a plan made three weeks earlier. Things change. You could have completely missed something in your customer research. Or, a technology in the stack can change, thus forcing your hand. But before rushing to add an additional requirement: i. ensure that it is absolutely necessary; and ii. understand how it will affect the feel and performance of the product as a whole. 3. Don’t get lazy. We were tired and distracted that fateful Sunday. We had been pushing hard while balancing life; for example, I took the call between my sister’s graduation party and a trip to the movies with my nieces. Under such circumstances, it’s easier to say “Go for it” than it is to ask the hard questions. But in reality, it is easier to be disciplined up-front than it is to unwind a mess caused by small-thinking. DiMaggio’s streak ended in th 57th game. The Patriot’s Perfect Season slipped away in the Super Bowl. And Spottah’s thrash ended a solid run of ships. But we’re a young team and the new season starts today. For the last five years, I have been immersed in technology. My journey began as a market analyst covering the technology needs and buying patterns of financial service companies. Currently, I help Teach For America budget and forecast its technology investments. Given the pace at which TFA invests in technology I have seen some amazing projects, most notably ERP and CRM implementations.

The amount I have learned in the last five years, however, does not sum to what I've learned in the last five weeks. Before Christmas, I began developing a mobile application with a team I met at NYU. I'll spare you the details until we launch in mid-February, but let's say we built and distributed a minimum viable product and the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. Having never worked on the product development side, the learning curve is steep. My biggest takeaway to date is deciding whether to invest in performance or functionality. Product novices take for granted that applications work reliably and securely. We log into Gmail and expect our emails to be there. We post a picture to Facebook and expect it to instantly appear in our feed. In other words, we take for granted what we cannot see. This is performance and it makes or breaks an application. Would you use Gmail if 1 out of every 100 emails got lost? Would Facebook be as popular if it took 15 seconds instead of 0.15 seconds to post a photo? On the other hand, product novices are quick to identify -- and long for -- missing features. We are accustomed to using complete products built by teams of engineers. We expect every bell and whistle, and get flustered when we are unable to do a seemingly easy task. We cannot imagine a product that is not integrated with Twitter or designed to send alerts. Functionality is what you see, and it too can make or break a product. Instagram is a great example; would the up-start be as successful without filters? Early-stage companies have limited resources and therefore must decide between better performance or more features. As I wrestle with this decision, I am reminded of my family friends. The husband drove a Jaguar and the wife drove a Porsche. When I got my license, they were kind enough to let me test their exotic vehicles. (My family had a Ford Taurus and a Mercury Grand Marquis so you could imagine my joy.) When I got into the Porsche, I was amazed at how sparse it was. It was basically an empty cockpit with a pathetic after-market stereo. Then I turned it on, put it in first gear, and slalomed through the back roads. Damn; it was the definition of performance. Then I got into the Jaguar. It had everything. Plush seats, a great stereo, beautiful wood paneling. It was comfortable and pretty but it didn't drive much better than my dad's Grand Marquis. And even worse, the Jaguar was always in the shop. In short, the Jag was all features and no performance. So as I discuss the development roadmap with my team, I remind myself it is better to be a Porsche than a Jaguar. A sparse product that works is better than a fully-loaded flop. |

JONATHAN STEIMAN

I'm the Founder and CEO of Peak Support. This blog is my take on early-stage companies and innovation. Every so often, there may be a post about culture, networking, family -- you name it. After all, what is a blog if it isn't a tad bit unstructured.

Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|