|

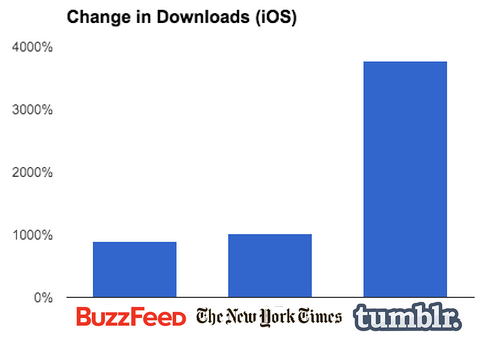

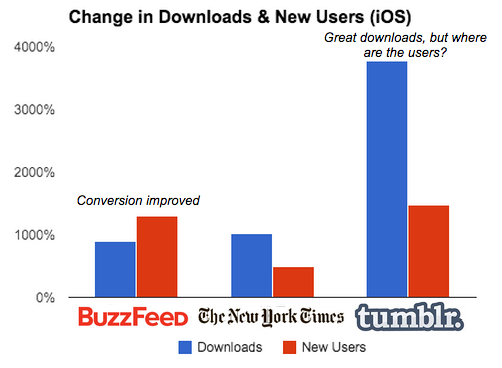

Every start-up dreams about being mentioned in The New York Times. A dash of NY Times ink provides credibility to your idea and drives usage, or so the logic goes. But in today's rapidly changing media landscape, does this still hold true? Based on my experience with TalkTo, the answer is a resounding NO. In fact, even large websites like BuzzFeed may not provide a huge boost to your business. The holy grail of driving traffic: raving fans writing genuine reviews for a small but passionate readership. I came to this conclusion by comparing how press coverage from three outlets improved our average daily iOS downloads. I looked at daily downloads 5 days prior to each article and 5 days after each article. TalkTo, which was acquired by Path in June, has been covered by many of the major publications but for this study I looked at mentions in The New York Times (Old Media), BuzzFeed (New Media), and Tumblr (Social Media). A Tumblr blog posted by an angsty 20-something from Canada named HeyitsJnnfr increased downloads by a factor of 38; in other words, if we got 1 download prior to the blog, we got 38 the following week. Jennifer nailed a particular use-case: "people who suffer from social anxiety where telephone communications might be triggering or uncomfortable." This message resonated with her 2,500 followers who started to like and reblog the post. As of today, this obscure blog has been shared by 89,000 people. In comparison, BuzzFeed, with 1.41 million Twitter followers and 3.8 million Facebook likes, drove a 10X increase in downloads. The New York Times (13 million Twitter, 8.5 million Facebook) drove slightly more downloads than BuzzFeed and but far fewer than Heyitsjnnfr's post. Downloads are only half of the battle. The other key element is conversion, i.e. the number of people that download, open and use the app. In this metric, BuzzFeed was the best. As you can see from the chart below, the 5-day before/after change in BuzzFeed New Users outpaced downloads. Tumblr, on the other hand, was pretty abysmal: A 38X increase in new users only yielded a 16X increase in New Users. The New York Times was similar to Tumblr. Key Take Aways

6 Comments

For the last few months, I have worked alongside my partner Jimmy Byrum and together we created some very successful Facebook mobile ads for TalkTo (iTunes, Google Play). Inc Magazine was interested in our insights. Check out this blog that appeared on Inc.com: CLICK HERE TO READ FULL POST.

Yesterday, Facebook released a roadshow video ahead of its IPO. The video highlights Facebooks’ opportunity to win more advertising dollars, and also points out the company’s role as a social platform. I’ve been thinking a lot about Facebook lately, so wanted to use this opportunity to jot down some notes.

Advertising First, Facebook has the potential to win a bigger chunk of the global advertising market. According to FB, brands spend about $600B on advertising per year. Global advertising spend is a slow-growth business; according to ZenithOptimedia ad spend will grow 4.8% from 2011 to 2012, which is roughly in-line with global GDP growth. Since the overall pie isn’t growing, FB needs to win ad spend from other areas, like television, radio and print. Will they be able do this? Hell yes. People are spending an increasing amount of time on Facebook, at the expense of other media. (Remember, the hours in day are static so time spent on FB equates to less time spent elsewhere.) And what is everyone doing during this time? They are watching videos, reading articles and listening to music. So without even factoring in that FB campaigns are extremely effective, FB will have no problem growing its advertising revenue. Platform The second opportunity is best described with a riddle: What is the only thing on the web that is unique and ubiquitous? Give up? It is your Facebook page. If you’re like me, you have three active email accounts and two phone numbers. But you only have one Facebook page. Thus, developers building social products have no choice but to integrate with Facebook. I found this out the hard way. When we first designed Spottah, which is currently being reviewed by Apple, we decided not to use Facebook Connect. We thought integrating with Facebook would diminish our value proposition of sharing photos among only close friends and family. So we decided to connect by email or phone; after all, close friends would know your email address. We pushed a beta. It was a disaster. No one knew which email address their friend signed up with. For example, I’m registered using my @spottah.com account but everyone was trying to connect with my @gmail.com account. We looked at our sharing process and realized we needed a purely unique identifier. It became immediately obvious that Facebook has a monopoly on unique identifiers and that we would have to integrate Connect. To my knowledge, Facebook has no plans to directly monetize Connect and Open Graph. The goal is to create an ecosystem in which independent developers create great apps that increase the value of both companies. While this makes sense, I could also see a world in which Facebook charges a small amount for Connect and Open Graph. As a developer, I would pay for this. When we started Spottah, I did not think twice about whipping out my credit card to buy computing power from Amazon, analytics from Mixpanel, and smarter email from MailChimp. But all of these are worthless without customers, which Facebook provides. Yet, customers acquired from Facebook are free. The idea of Facebook charging developers is controversial. Many would point to Microsoft as a parallel example. Microsoft never charged its independent developers. A strong supply of programs designed for Windows meant more sales of Windows. This in turn increased the demand for PCs, which Microsoft capitalized on by grabbing the largest chunk of value chain. Microsoft and Facebook are not parallel examples, however. Microsoft had greater control. For Microsoft, the better the ecosystem the greater the sales of PCs. Plain and simple. Facebook, on the other hand, does not have as great of control. Instagram is the perfect example. Facebook enabled Instagram’s rapid growth by improving connections and spreading the word via Newsfeed postings. In the end, Instagram became so compelling that people were visiting Instagram before Facebook, and also spending more time on the app. Realizing this, Facebook bought Instagram, proving that Instagram captured the lion’s share of the value. Instagram will not be the last company to capture a greater portion of the value than Facebook. The key for Facebook will be designing a structure in which they foster independent development but are also able to capture their share of the value created. Today's Wall Street Journal celebrated the life of Ted Fortsmann. Fortsmann was one of the founding fathers of private equity and a prominent 'character' in "Barbarians at the Gate," a must-read about the RJR Nabisco buyout.

I'm writing about Fortsmann because his firm perfectly summarized what it means to be an entrepreneur. According to the Journal, Fortsmann Little gave their guests at a 25th Anniversary celebration a silver platter engraved with the following: "The entrepreneur, as a creator of the new and a destroyer of the old, is constantly in conflict with convention. He inhabits a world where belief precedes results, and where the best possibilities are usually invisible to others. His world is dominated by denial, rejection, difficulty, and doubt. And although as an innovator, he is unceasingly imitated when successful, he always remains an outsider to the 'establishment.'" This quote perfectly captures entrepreneurship. The opening line - "creator of new and destroyer of the old" - details the phenomena of creative destruction. The second sentence captures the imaginative nature of entrepreneurs; I'm immediately reminded of Steve Jobs who envisioned a world in which every person would have a computer in light of the day's leading tech firms (HP, IBM, Xerox) telling him the computer was a business tool. The third sentence encapsulates the difficult path entrepreneurs traverse. Examples of struggles are bountiful, but my favorite is the Music Genome Project; before pivoting to become Pandora, the company burned through its cash and asked employees to take no pay for a year. The final sentence is interesting. The imitator effect has a positive but hard to measure impact on the economy. The success of one entrepreneur motivates thousands to strike out on their own to seek opportunities "usually invisible to others." Prior entrepreneurial successes, in other words, signal to current would-be entrepreneurs that the system works. One person in the new class of entrepreneurs then realizes wild success and the cycle repeats itself. If Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were stripped of their wealth or thrown in prison for challenging the statues quo, would Larry and Sergey have been motivated to start Google? And if Larry and Sergey were not able to capture the value they created, would Mark Zuckerberg have been motivated enough to create Facebook? A few weeks ago our friend from Delhi, India visited. As a WSJ reporter, Shefali is naturally inquisitive, so she asked: "Jon, what was your reaction to the Bin Laden death?"

After some thought, I responded: "It made me realize exactly how much technology has changed over the past decade." Flash back to Tuesday September 11, 2001. I was driving from Jackson, MI to Mackinac Island. I was anxiously watching the clock because at 9 AM I needed to find a store that sold CDs. Bob Dylan's Love And Theft album was dropping; as a huge Dylan fan I could not wait to hear the follow-up to the near flawless Time Out of Mind. I pulled off at a few exits but came up empty. Finally, I found a Walmart in Mt. Pleasant. I was no more than fifteen feet into the Supercenter when a man came up to me. "We're under attack!" "What?" I asked the man. He was straddling the line between burly and obese, and dressed in camouflage. "They - Saudi Arabia - or one of those countries - attacked New York." To this day, I'm still impressed that the man fingered Islamic extremists. My initial reaction, I'm embarrassed to say, was Russia, maybe China. A decade since the end of the Cold War and that was still my lens. After digesting the news in the electronics section, we canceled the Mackinac trip and turned back to Jackson. When we arrived home, we tuned into cable news. Like fifty percent of the homes in the nation, the house did not have Internet. With the Towers felled, the Pentagon ablaze and a mysterious plane down in Pennsylvania I was left with one final task: find out how my friends in New York and Washington were doing. I paced around the house, dialing friend after friend on an old, clunky cordless phone. At 7 PM, I switched to my Motorola StarTac. Flash forward to May 1, 2011. In many ways, very little has changed. We still put pants on in the morning, use a stove to cook breakfast, a car to get around. When it is hot, we put on air conditioning; when it is cold we turn up the thermostat. The way we gather and share information, however, has changed dramatically. Music is the first example. September 2001 was the crossroads for the music industry. In the preceding months, Napster launched, disrupted the music industry forever, and then shuttered. The world had a taste for digital distribution but there was no easy-to-use, reliable portable music system. That would not happen for another two months: Apple shipped the first iPod on November 10, 2001. So on that fateful morning when I wanted my Dylan, I knew the CD would soon be anachronistic but it was the only solution. And I wasn't alone. Music sales hovered around $14b in 2001. Today, sales are half that and falling precipitously. Perhaps the biggest revolution during the 10 years between September 11 and Bin Laden's death is the ubiquity of the Internet and the platforms it has enabled. In 2001, it was completely normal for a middle-class, educated home in the richest nation on the planet to not have Internet. Now, not only do most American's have Internet but the Internet has become accessible and powerful in developing nations, such as Pakistan. Over the last decade, Internet access in Pakistan has grown 1,000-fold to reach 10% of the population, or about 17 million people. In short, we've gone from a world where a comfortable American could not email friends from home to one in which a man in Abbottabad, Pakistan can broadcast - in real time and at zero cost - the raid on Bin Laden's compound. Lastly, and most obviously, the way we connect has changed. In 2001, communication was "one-to-one," meaning I called or emailed friend X, then friend Y and so on. Facebook and Twitter, which would not be invented for another two and half years and five years, respectively, enable "one-to-many" communications. These services are incredibly efficient during times of distress. Had Facebook been as ubiquitious as it is today, it would have taken me just a few seconds to learn the status of the dozen or so people I knew in New York. |

JONATHAN STEIMAN

I'm the Founder and CEO of Peak Support. This blog is my take on early-stage companies and innovation. Every so often, there may be a post about culture, networking, family -- you name it. After all, what is a blog if it isn't a tad bit unstructured.

Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|