|

Holman W. Jenkins, Jr of the Wall Street Journal wrote a spot-on analysis of Facebook. Check out Guess What? Facebook Is Speculative.

My two favorite quotes: "Facebook went public at $105 billion and Friday was selling at $87 billion. At either figure, Facebook's valuation is a projection of a revenue model that doesn't yet exist and hasn't even been articulated by the company. Buying shares at these prices is a bet on capitalist incentive eventually to find a way to turn Facebook into gold. But it's no sure thing. An investor who didn't understand this can find the man who cheated him in the mirror." "[Zuckerberg's] next trick will be to build a bridge between this data and the existing world of ad-supported media that all of us are immersed in every day....It requires of Mr. Zuckerberg a second act of entrepreneurial creation on the order of his first. But a place to start might be finding out who advised Steve Jobs on how to sell the record companies on iTunes. That person probably belongs on the Facebook payroll pronto."

10 Comments

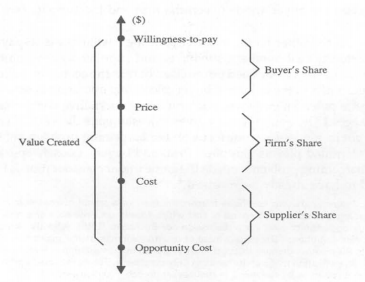

Today, is a “turning point” day. Yesterday, Spottah went live on the Apple app store. For more than two years, I have wanted to play the mobile game, so yesterday was an enormous milestone. Tomorrow, I will receive my diploma from New York University’s Stern School of Business. For three years, I attended Stern at night while working during the day. So as I close one chapter and open another, I want to take a moment to share my most memorable lessons from Stern's classrooms. The goal of the MBA is to teach students frameworks in which to tackle real world problems. We covered a ton of frameworks but here are my three favorites. The Value Chain It is easy to grasp that profits rise when you increase revenue and reduce costs. But what does that actually look like in an interconnected supply chain? Enter the The Value-Based Business Strategy by Adam Brandenburger and Harborne W. Stuart, Jr. Every firm sits in the middle of the value chain at some point. The firm buys resources from suppliers (raw materials, labor), turns those resources into a higher-value product, then sells that product to a buyer. Let’s use a clothing company, for example. The company buys fabric from a supplier and hirers workers. Inside the firm, workers turn raw fabric into fabulous garments. The firm then sells those garments at a higher cost to a retail store. In the diagram below, this transaction is marked by the “cost” and the “price.” Pretty straight forward. Here is where the value-based strategy comes into play. The total value of the chain is the buyer’s willingess-to-pay MINUS the supplier’s opportunity cost. The goal of a company is to capture as much of the value chain as possible. This means pushing the cost of inputs downwards to the supplier’s opportunity cost, i.e. the point right before it makes sense for the supplier to walk away and not make the sale. The same thing goes on the buyer side. The goal of the firm is to push upwards the price of its goods to the buyer’s willingness-to-pay. Vibram soles and Intel chips are great examples. Traditionally, these two products were commodities; no one cared about the sole of their shoe or the chip in their computer. As a result, the bootmakers and computer manufacturers captured the lion share of the value in the chain, i.e. there was a big spread between the price charged by Vibram/Intel and willingness-to-pay of Asolo/Dell. So what did Vibram and Intel do? They branded the components. Vibram advertised and put the bright yellow marker on each of its soles. Intel advertised, too, most famously creating the “Intel Inside” campaign. Customers soon demanded the yellow brand on their soles and wanted to know if Intel was inside their PC. This shifted the value away from the end manufacturer and towards the component maker, thus allowing Vibram and Intel to push towards the buyer’s willingness-to-pay point. The Value Formula

Sticking to value, but this time we’re are talking my favorite topic: Finance. Whenever new information arises and I’m trying to value an asset (stock, bond, property, you name it), I rely on a piece of advice from my valuation professor. “When new information comes to light ask yourself: what lever of the ‘value’ formula is being affected?” More specifically, the professor was referring to the perpetuity discounted cash flow (DCF) formula, which is: Value = Cash Flow / (Cost of Capital - Growth Rate of Cash Flows). The levers are the cash flows generated by the asset, the growth rate of those cash flows, and the opportunity cost of capital, i.e. the minimum return acceptable to investors. The purpose of the formula is to discount future cash flows into a net present value. The formula is not perfect, mainly because it assumes constant growth in cash flows, but it is an excellent rule of thumb. To put this in perspective, let’s say you own stock in a Company X. News breaks that the company lost a major contract. What lever is being affected? Cash flow; the company will generate less cash than before. One could also argue that cost of capital is at risk of rising, assuming a reduction in cash flows reduces the company’s chance of survival and thus increases the risk level. But the main lever being pulled is cash flow. Let’s put some numbers to this. Assume before the news, total cash flows were $100, cost of capital was 10% and growth was 3%. Thus, the asset is worth $1,428 (100 / (10%-3%)). Having lost the contract, cash flows are estimated to fall to $75, which causes the value of the company to fall to $1,071 ($75 / (10%-3%)). This is super simple finance but it a great framework to understand quickly how certain events affect asset prices. In short, always ask “what lever is being pulled: cash, cost of capital, growth?” The Growth Diamond So far, the frameworks have been very quant-ey -- my apologies. So let me finish strong with a framework taught by Robert Wright that explains why some countries develop rapidly, like the United States, while others do not develop at all. It comes down to the “Growth Diamond;” Stern professors notoriously love baseball. Home plate is a non-predatory, Lockean government. In other words, growth starts with a government that protects the life, liberty and property of its citizens. Such a government collects taxes transparently, regularly and at a reasonable rate. The government also establishes and enforces reasonable laws. Note that such a government does not need to be a democracy; though they often are. The next phase of development, or first base, is a financial system in which capital moves from savers to borrowers. First base cannot be reached without home plate; after all, the crux of saving and lending are contracts recognized by the courts established by the government. With home plate and first base established, the economy is prepared to take second base: entrepreneurship. Individual actors are comfortable investing into a long-term business knowing that the government will not pilfer it in the night. And even if something goes wrong, the actor has faith that the slip of paper called “insurance” will be made good. And lastly, the actor has access to capital, thanks to first base. Interestingly, not all economies move equally between bases. There are countries with non-predatory governments and financial systems that have less entrepreneurship than others. The final stage, third base, is a management system. Basically, the entrepreneurs that flourished from a stable government and access to capital eventually grow into large, distributed organizations. These organizations have the systems required to undertake large and complex markets like air travel, chip fabrication and automobile manufacturing. I find this framework incredibly helpful as I look at emerging markets. The first question is what type of government does the country in question have? If the answer is non-predatory, than you can begin to look down the base path. The growth diamond is also good for understanding domestic policy. I find myself asking how will a new law or regulation effect any of the bases. In closing, the MBA education was amazing. As I think about more frameworks and lessons, I will do my best to share. Yesterday, Facebook released a roadshow video ahead of its IPO. The video highlights Facebooks’ opportunity to win more advertising dollars, and also points out the company’s role as a social platform. I’ve been thinking a lot about Facebook lately, so wanted to use this opportunity to jot down some notes.

Advertising First, Facebook has the potential to win a bigger chunk of the global advertising market. According to FB, brands spend about $600B on advertising per year. Global advertising spend is a slow-growth business; according to ZenithOptimedia ad spend will grow 4.8% from 2011 to 2012, which is roughly in-line with global GDP growth. Since the overall pie isn’t growing, FB needs to win ad spend from other areas, like television, radio and print. Will they be able do this? Hell yes. People are spending an increasing amount of time on Facebook, at the expense of other media. (Remember, the hours in day are static so time spent on FB equates to less time spent elsewhere.) And what is everyone doing during this time? They are watching videos, reading articles and listening to music. So without even factoring in that FB campaigns are extremely effective, FB will have no problem growing its advertising revenue. Platform The second opportunity is best described with a riddle: What is the only thing on the web that is unique and ubiquitous? Give up? It is your Facebook page. If you’re like me, you have three active email accounts and two phone numbers. But you only have one Facebook page. Thus, developers building social products have no choice but to integrate with Facebook. I found this out the hard way. When we first designed Spottah, which is currently being reviewed by Apple, we decided not to use Facebook Connect. We thought integrating with Facebook would diminish our value proposition of sharing photos among only close friends and family. So we decided to connect by email or phone; after all, close friends would know your email address. We pushed a beta. It was a disaster. No one knew which email address their friend signed up with. For example, I’m registered using my @spottah.com account but everyone was trying to connect with my @gmail.com account. We looked at our sharing process and realized we needed a purely unique identifier. It became immediately obvious that Facebook has a monopoly on unique identifiers and that we would have to integrate Connect. To my knowledge, Facebook has no plans to directly monetize Connect and Open Graph. The goal is to create an ecosystem in which independent developers create great apps that increase the value of both companies. While this makes sense, I could also see a world in which Facebook charges a small amount for Connect and Open Graph. As a developer, I would pay for this. When we started Spottah, I did not think twice about whipping out my credit card to buy computing power from Amazon, analytics from Mixpanel, and smarter email from MailChimp. But all of these are worthless without customers, which Facebook provides. Yet, customers acquired from Facebook are free. The idea of Facebook charging developers is controversial. Many would point to Microsoft as a parallel example. Microsoft never charged its independent developers. A strong supply of programs designed for Windows meant more sales of Windows. This in turn increased the demand for PCs, which Microsoft capitalized on by grabbing the largest chunk of value chain. Microsoft and Facebook are not parallel examples, however. Microsoft had greater control. For Microsoft, the better the ecosystem the greater the sales of PCs. Plain and simple. Facebook, on the other hand, does not have as great of control. Instagram is the perfect example. Facebook enabled Instagram’s rapid growth by improving connections and spreading the word via Newsfeed postings. In the end, Instagram became so compelling that people were visiting Instagram before Facebook, and also spending more time on the app. Realizing this, Facebook bought Instagram, proving that Instagram captured the lion’s share of the value. Instagram will not be the last company to capture a greater portion of the value than Facebook. The key for Facebook will be designing a structure in which they foster independent development but are also able to capture their share of the value created. |

JONATHAN STEIMAN

I'm the Founder and CEO of Peak Support. This blog is my take on early-stage companies and innovation. Every so often, there may be a post about culture, networking, family -- you name it. After all, what is a blog if it isn't a tad bit unstructured.

Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|