|

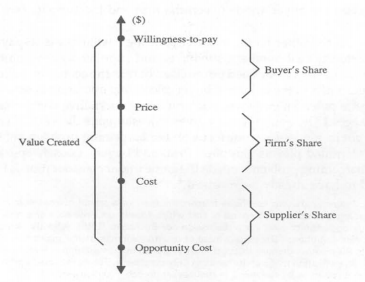

Today, is a “turning point” day. Yesterday, Spottah went live on the Apple app store. For more than two years, I have wanted to play the mobile game, so yesterday was an enormous milestone. Tomorrow, I will receive my diploma from New York University’s Stern School of Business. For three years, I attended Stern at night while working during the day. So as I close one chapter and open another, I want to take a moment to share my most memorable lessons from Stern's classrooms. The goal of the MBA is to teach students frameworks in which to tackle real world problems. We covered a ton of frameworks but here are my three favorites. The Value Chain It is easy to grasp that profits rise when you increase revenue and reduce costs. But what does that actually look like in an interconnected supply chain? Enter the The Value-Based Business Strategy by Adam Brandenburger and Harborne W. Stuart, Jr. Every firm sits in the middle of the value chain at some point. The firm buys resources from suppliers (raw materials, labor), turns those resources into a higher-value product, then sells that product to a buyer. Let’s use a clothing company, for example. The company buys fabric from a supplier and hirers workers. Inside the firm, workers turn raw fabric into fabulous garments. The firm then sells those garments at a higher cost to a retail store. In the diagram below, this transaction is marked by the “cost” and the “price.” Pretty straight forward. Here is where the value-based strategy comes into play. The total value of the chain is the buyer’s willingess-to-pay MINUS the supplier’s opportunity cost. The goal of a company is to capture as much of the value chain as possible. This means pushing the cost of inputs downwards to the supplier’s opportunity cost, i.e. the point right before it makes sense for the supplier to walk away and not make the sale. The same thing goes on the buyer side. The goal of the firm is to push upwards the price of its goods to the buyer’s willingness-to-pay. Vibram soles and Intel chips are great examples. Traditionally, these two products were commodities; no one cared about the sole of their shoe or the chip in their computer. As a result, the bootmakers and computer manufacturers captured the lion share of the value in the chain, i.e. there was a big spread between the price charged by Vibram/Intel and willingness-to-pay of Asolo/Dell. So what did Vibram and Intel do? They branded the components. Vibram advertised and put the bright yellow marker on each of its soles. Intel advertised, too, most famously creating the “Intel Inside” campaign. Customers soon demanded the yellow brand on their soles and wanted to know if Intel was inside their PC. This shifted the value away from the end manufacturer and towards the component maker, thus allowing Vibram and Intel to push towards the buyer’s willingness-to-pay point. The Value Formula

Sticking to value, but this time we’re are talking my favorite topic: Finance. Whenever new information arises and I’m trying to value an asset (stock, bond, property, you name it), I rely on a piece of advice from my valuation professor. “When new information comes to light ask yourself: what lever of the ‘value’ formula is being affected?” More specifically, the professor was referring to the perpetuity discounted cash flow (DCF) formula, which is: Value = Cash Flow / (Cost of Capital - Growth Rate of Cash Flows). The levers are the cash flows generated by the asset, the growth rate of those cash flows, and the opportunity cost of capital, i.e. the minimum return acceptable to investors. The purpose of the formula is to discount future cash flows into a net present value. The formula is not perfect, mainly because it assumes constant growth in cash flows, but it is an excellent rule of thumb. To put this in perspective, let’s say you own stock in a Company X. News breaks that the company lost a major contract. What lever is being affected? Cash flow; the company will generate less cash than before. One could also argue that cost of capital is at risk of rising, assuming a reduction in cash flows reduces the company’s chance of survival and thus increases the risk level. But the main lever being pulled is cash flow. Let’s put some numbers to this. Assume before the news, total cash flows were $100, cost of capital was 10% and growth was 3%. Thus, the asset is worth $1,428 (100 / (10%-3%)). Having lost the contract, cash flows are estimated to fall to $75, which causes the value of the company to fall to $1,071 ($75 / (10%-3%)). This is super simple finance but it a great framework to understand quickly how certain events affect asset prices. In short, always ask “what lever is being pulled: cash, cost of capital, growth?” The Growth Diamond So far, the frameworks have been very quant-ey -- my apologies. So let me finish strong with a framework taught by Robert Wright that explains why some countries develop rapidly, like the United States, while others do not develop at all. It comes down to the “Growth Diamond;” Stern professors notoriously love baseball. Home plate is a non-predatory, Lockean government. In other words, growth starts with a government that protects the life, liberty and property of its citizens. Such a government collects taxes transparently, regularly and at a reasonable rate. The government also establishes and enforces reasonable laws. Note that such a government does not need to be a democracy; though they often are. The next phase of development, or first base, is a financial system in which capital moves from savers to borrowers. First base cannot be reached without home plate; after all, the crux of saving and lending are contracts recognized by the courts established by the government. With home plate and first base established, the economy is prepared to take second base: entrepreneurship. Individual actors are comfortable investing into a long-term business knowing that the government will not pilfer it in the night. And even if something goes wrong, the actor has faith that the slip of paper called “insurance” will be made good. And lastly, the actor has access to capital, thanks to first base. Interestingly, not all economies move equally between bases. There are countries with non-predatory governments and financial systems that have less entrepreneurship than others. The final stage, third base, is a management system. Basically, the entrepreneurs that flourished from a stable government and access to capital eventually grow into large, distributed organizations. These organizations have the systems required to undertake large and complex markets like air travel, chip fabrication and automobile manufacturing. I find this framework incredibly helpful as I look at emerging markets. The first question is what type of government does the country in question have? If the answer is non-predatory, than you can begin to look down the base path. The growth diamond is also good for understanding domestic policy. I find myself asking how will a new law or regulation effect any of the bases. In closing, the MBA education was amazing. As I think about more frameworks and lessons, I will do my best to share.

2 Comments

|

JONATHAN STEIMAN

I'm the Founder and CEO of Peak Support. This blog is my take on early-stage companies and innovation. Every so often, there may be a post about culture, networking, family -- you name it. After all, what is a blog if it isn't a tad bit unstructured.

Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|